Bernstein’s Candide

Candide take #1: what happened in Boston?

Candide opened in Boston for three weeks of tryouts. The dress rehearsal overran catastrophically and the reviewers were asked to come back later in the week. “We have a little trouble,” Tony Guthrie (the director) told the charity benefit audience in his disarming way, “but we’re going to get this thing on tonight.” Variety’s account, when it came, began promisingly: “It’s a spectacular, opulent and racy musical, verging on operetta. It’s replete with eye-filling costumes, lavish settings, a big cast and fine musical score.”

Many other Boston reviewers were enthusiastic about Candide, but the book was criticized for being slow and heavy and hard to follow. Behind the scenes the mood was close to panic. When associate producer Lester Osterman came up from New York to see a performance, he arrived late, in time to catch only the last fifteen minutes: “I was almost knocked down by the people trying to get out of the theater,” he told a crisis meeting next morning.

Bernstein and Hellman pruned to clarify the show and wrote extra material to provide time for costume changes. An especially hectic period began when it was decided that a new number was needed to brighten up the start of the scene in the Venice casino.

Script conferences, Richard Wilbur remembers, took place in the men’s room at the theater. “Let’s do a vulgar rousing number,” Bernstein said. He wanted the kind of song that might be sung on the way to a college football game — but with echoes of “Carnival in Venice“. The result was “What’s the Use?”. Bernstein improvised a refrain there and then, after which he and Wilbur went back to their separate hotels; every hour or so Wilbur would phone through another verse or a refinement to an existing idea. Hershy Kay came up from New York the same day to do the orchestrations, and that evening the number was part of the show. [1]

The origins of Candide

It’s difficult to believe nowadays that Candide had such a difficult start: being one of Bernstein’s most performed works, one is bound to imagine that things were at least in place, if not perfect, from the beginning. It is however quite a common thing. If we look back at the history of the opera, a great number of what we know today as masterpieces opened in disaster: bad reviews, unhappy audience, months if not years of coming adjustments and corrections by its creator(s). Candide was virtually complete in August 1956 and, up to that point, it was Bernstein’s highest achievement as a composer: two full hours of music filled with solos, duets, trios, quartets, ensembles, choruses and purely orchestral music, intertwined with spoken dialogue.

Voltaire vs Hellman

Lillian Hellman and Leonard Bernstein saw in Candide a good way to hit back on Eisenhower’s America. Voltaire’s however made use of the sharp pen of satyrs to mock the philosophy of the “all’s for the best in the best of all possible worlds“: short sentences in short chapters, filled with wittiness, cynicism and cleverness. Hellman’s expertise was everything but: her strong suit was a three-act play and had never composed a comedy. Yet, her deep sense of theater and her anger towards America’s politics led her to produce an admirable script. Surely Bernstein would have not agreed to collaborate with her had he not believed in her skills.

Candide is “based on” Voltaire. In Hellman’s script there is a number of situations and places that are not featured in Voltaire’s novel: the casino in Venice, the waltz in Paris, Dr. Pangloss and Martin are played by the same actor. But then again, this is a common denominator to a lot of operas and musical theater works inspired by a novel or a theatrical piece. Take Tosca for instance: the original five acts drama by Victorien Sardou was reduced to three and many of the historical events and characters were cut off from the libretto. It doesn’t make Tosca less valuable as a whole: in the same way Hellman’s work is a take on Voltaire’s, adapted to the situations and perceptions of the America of the 50s.

On a side note, some additional lyrics were written later by another great American lyricist: Stephen Sondheim.

The music

Candide’s score was described by Bernstein as a Valentine card to European music: dance forms like the Polka and the Mazurka, the Gavotte and the Waltz fill the score from the beginning to the end. Naturally, there’s plenty of references to the European tradition of opera as well: although it was at the time suggested that Bernstein was mocking opera, this is not true.

The use of opera artifices is wide, but functional to the action and the character. Take Cunegonde’s aria “Glitter and be gay” for instance: it is a closed aria in the perfect spirit of traditional Italian operas. It makes use of parody, both in the text and the music, to exacerbate the character itself. The use of coloratura here is not a mockery towards traditional operas, it is pure musical humor used to convey Cunegonde’s features. A brilliant example of Bernstein’s composing dexterity.

I would like to close this post with a video by a very young and talented singer: Jessey-Joy Spronk, who will be performing at the October 1st concert for the Kunst en Kunstig Festival, interpreting “Glitter and be gay”.

Sources:

[1] – Leonard Bernstein, a biography by Humphrey Burton

A guide to Leonard Bernstein’s Candide

Leonard Bernstein official website

Leonard Bernstein: a total embrace of music

Voltaire foundation – University of Oxford

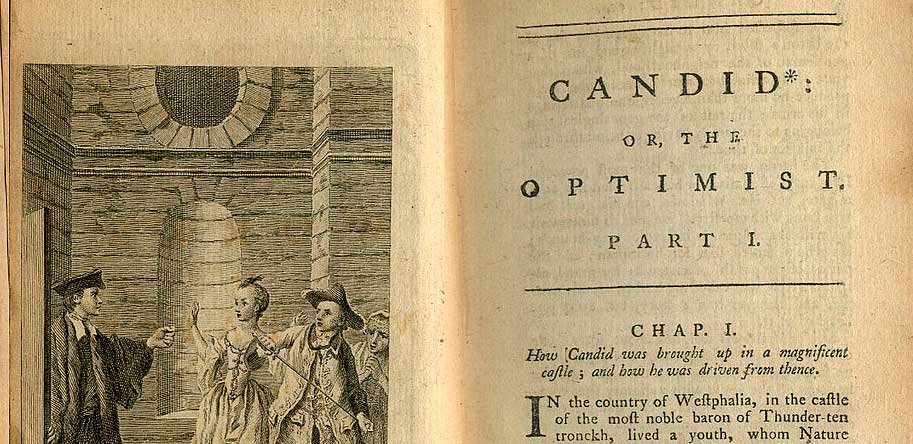

Frontispiece of an English translation of 1762, image by James Gwin, designer; John Hall (1739–1797), engraver (Private Collection of S. Whitehead) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

About the author

Gianmaria Griglio

Composer and conductor, Gianmaria Griglio is the co-founder and Artistic Director of ARTax Music.

Interested in some more music? Take a look at this series!