Puccini A to Z – La bohème

B as in La Bohème

La Bohème is one of those operas that almost everyone has heard of.

According to various statistics, it has an average of 5-600 productions per season around the world, which makes it one of the most performed operas ever.

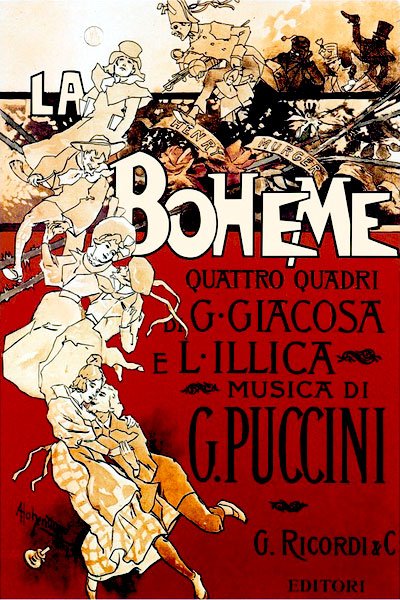

This four-acts opera was based on the Scènes de la vie de bohème by Henri Murger and adapted for the theater by the great librettists Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. La Bohème was premiered at the Teatro Regio in Turin on February 1st,1896 conducted by the young Arturo Toscanini.

Productions in 2015/2016

Performances in 2015/2016

Some history

The initial response of the audience at the first performance was quite warm while critics’ reactions were extremely negative; for example Carlo Bersezio wrote on the newspaper La Stampa:

“[Puccini cannot be forgiven for] composing his music hurriedly and with very little effort to select and polish.. … [The work contains] music that can delight but rarely move. …

Even the Finale of the opera, so intensely dramatic in situation, seems to me deficient in musical form and color. …

La Bohème, even as it leaves little impression on the minds of the audience, will leave no great trace upon the history of our lyric theater, and it will be well if the composer returns to the straight road of art, persuading himself that this has been a brief deviation.” [1]

Despite the adversity of the critics, the opera became extremely popular very quickly with new productions mounted by the Teatro San Carlo of Naples (14 March 1896), the Teatro Comunale of Bologna (4 November 1896), the Teatro Costanzi of Rome (17 November 1896), La Scala of Milan (15 March 1897) and all the other major theaters in Italy and in the world.

The libretto and the missing act

Giuseppe Giacosa, Giacomo Puccini and Luigi Illica

The preparation of the libretto was quite long, especially due to the challenge of adapting the situations and characters of the original text to the framework of an opera.

Originally the opera was conceived in 5 acts by Illica and Giacosa: in order to explain the jealousy of Rodolfo’s in act 3, an “extra” act was to be inserted after act 2. The act was set to a party at Musetta’s where Mimí was to be introduced to the Viscount that Rodolfo mentions in act 3.

The “missing act” was discovered in 1957 when Illica’s widow died leaving her husband’s papers to the Parma Museum. Puccini decided not to include it in the opera.

A defiance on La Bohème: Puccini vs Leoncavallo

“Scènes de la vie de bohème” was published for the first time in the french magazine “Le Corsair-Satan”, very popular in the 1840s: they were a series of short stories with a quite feeble narrative arch, though still gripping. Its real fortunes came with the production of the drama “La vie de bohème” which encountered the favors of growing audiences around Europe. Both Puccini and Ruggero Leoncavallo, the famous composer of Pagliacci, grew fond of the plot, enough to think about setting it to music.

And there it was: a real challenge, made up of many rivalries, a pinch of envy, and even some cheap shot. It seems that Puccini’s enthusiasm for the topic was born shortly after the first performance of Manon Lescaut (February 1st, 1893). Indeed, Puccini himself spoke convincingly to a lawyer, Carlo Nasi, and a journalist during a train trip from Turin to Milan, where he was to attend the debut of the latest opera by Giuseppe Verdi, Falstaff. Nasi suggested to plot out the scenes himself and for the journalist to write the verses. Fate, however, required that Puccini and Leoncavallo would soon meet at the De Cristoforis Gallery in Milan.

The two found out that they had the same interest: Leoncavallo, extremely upset, set out to make clear he had “right of way” through a media strategy with the help of his editor, Edoardo Sonzogno: the newspaper “Il Secolo” announced the new opera by the beloved composer of Pagliacci while another newspaper, the “Corriere della Sera” had already 1894 as the year of the premiere, pointing out how Puccini was just starting to get interested in the subject of La Bohème while Leoncavallo had already worked on it for a few months.

And more: “Maestro Leoncavallo wishes to make known that he signed a contract for the new opera, and has since then been working on the music for that subject [La Bohème]…. Maestro Puccini, to whom Maestro Leoncavallo declared a few days ago that he was writing Bohème, has confessed that only on returning from Turin a few days ago did he have the idea of setting La Bohème and that he spoke of it to Illica and Giacosa, who he says have not yet finished the libretto. Thus Maestro Leoncavallo’s priority over this opera is indisputably established. ” – Il Secolo, 20-21 March 1893

Puccini couldn’t care less: he didn’t want to cause any trouble to a fellow colleague but at the same time he had no intention of backing off.

“He will write the music. I will write the music. The audience will judge.”

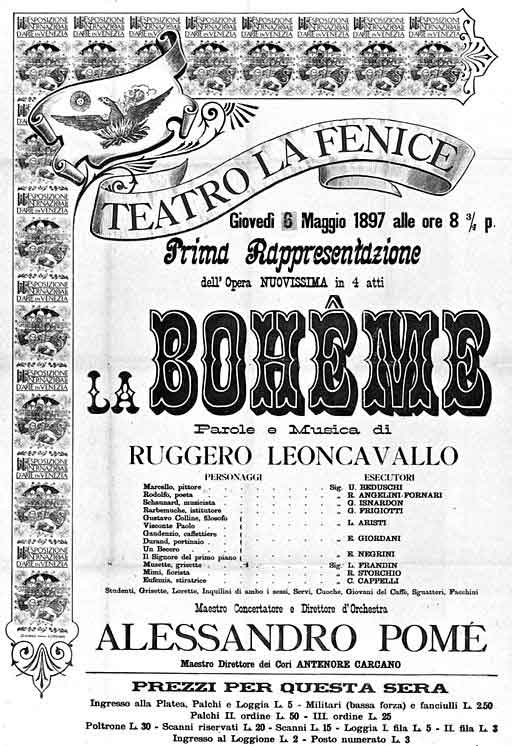

As it turned out, Puccini finished before Leoncavallo: Puccini’s opera premiered on February 1st, 1896 while Leoncavallo’s on May 6th, 1897. Even though Leoncavallo’s take was very well received, even better that Puccini’s, in the end the latter made it through history. Puccini’s balance of emotions throughout the opera is far more successful, while Leoncavallo went for a lighter approach in the first part painting the second half of the work continuously in darker shades.

Incidentally, Leoncavallo’s version makes use of that part of the plot that went in Puccini’s missing act.

Act 1 or Quadro I

In a garret

It’s Christmas’ eve: Marcello, the painter, is painting the red sea while Rodolfo, the poet, is trying to light up the fire with one of his poems. Colline, the philosopher, joins in. Eventually, Schaunard, the musician, makes his triumphant entrance with a basket full of food and wine, bearing the good news of having earned some money. The party is interrupted by the unexpected visit of Benoît, the landlord, coming to collect the rent, but the four get rid of him with a trick. It’s almost evening and they decide to take the party to the cafè Momus. Rodolfo stays, promising to join them after finishing an article for the newspaper “Il Castoro”.

Alone, Rodolfo hears a knock on the door. A female voice asks to come in and light up her candle. It’s Mimì, the neighbor. Rodolfo lets her in and helps her out, but Mimì almost faints: it’s the first sign of the tuberculosis. She’s quickly back on her feet, but as she’s about to leave she realizes that she’s lost the key to her room. Both of them start searching for it, kneeling on the floor. Rodolfo finds it first, but he hides it, anxious to spend some more time with her. His hand touches hers, opening to two of the most famous and beautiful arias in the history of opera: “Che gelida manina”, sung by Rodolfo, and “Mi chiamano Mimì”.

The scene is interrupted by Rodolfo’s friends, calling him from the street. He would like to stay and spend some more time with her, but she suggests they both go. Rodolfo and Mimì leave the garret together as lovers.

Act 2 or Quadro II

Latin Quartier and cafè Momus

A great crowd, including children, has gathered with street sellers trying to attract buyers. Rodolfo and Mimì join the other bohèmiens. Rodolfo buys her a pink bonnet. While they sit at Momus, Musetta, an old flame of Marcello, comes in with the old and rich Alcindoro. She recognizes Marcello and tries everything to catch his attention – another famous aria comes at this point: “Quando men vo”. Mimì recognizes that Musetta is still in love with Marcello. Musetta pretends to be suffering from a tight shoe and sends him to the shoemaker to get her shoe mended. Alcindoro leaves, and Musetta and Marcello fall into each other’s arms. When the bill comes Schaunard’s purse is missing and they have no money to pay. Musetta has the entire bill charged to Alcindoro. The sound of a military band is heard, and the friends leave, including Musetta. Alcindoro returns with the repaired shoe and the waiter hands him the bill.

Act 3 or Quadro III

At the toll gate at the Barrière d’Enfer

It’s late February, it’s snowing. Living together has become impossible: the fights between Marcello and Musetta are constant and the relationship between Rodolfo and Mimì is not doing too well either. Mimì comes in trying to find Marcello, currently living in a tavern, painting signs for the innkeeper. She confides in him and tells him about Rodolfo’s jealousy. Marcello tells her that Rodolfo is asleep inside. As he wakes up and comes out, Mimì hides. At first, Rodolfo tells Marcello he has left Mimì because of her coquettishness, but he eventually confesses that his jealousy is a cover: he fears she is slowly being consumed by a deadly illness and the life in the garret doesn’t help. He hopes to be able to push Mimì in the arms of some wealthier suitor.

Mimì has heard everything. Her weeping and coughing reveal her presence, and Rodolfo hurries to her. Marcello goes back inside. Mimì and Rodolfo want to separate amicably, but they find the breaking up in winter in would be like dying and they agree to stay together till the flower season.

Act 4 or Quadro IV

Back in the garret

Both Marcello and Rodolfo broke up with their girlfriends. They try to work, but mostly they talk about their suffering. When Colline and Schaunard join them, a bit of the joyous atmosphere of act 1 comes back in, but the jokes are only a mask to their disillusions. Suddenly Musetta enters: she bumped into Mimì, who had taken up with a wealthy viscount after leaving Rodolfo in the spring, and has now left him. Mimì, severely weakened by her illness, begged Musetta to take her to Rodolfo.

Musetta sends Marcello to sell her own earrings to buy medicines, and goes out herself looking for a muff to warm Mimì’s cold hands. Colline follows, deciding to sell his overcoat.

Rodolfo and Mimì remember their past happiness and their first meeting, in that same garret. The others return and Mimì gently thanks Rodolfo for the muff, which she believes is a present from him, reassuring him that she is better and falls asleep. Nobody initially realizes that she has, in fact, died. Schaunard is the first one to find out. Rodolfo rushes to the bed, calling Mimì’s name in anguish, weeping helplessly as the curtain falls.

Discography

There are almost 300 recordings of La Bohème and the number keeps growing. The very first one dates back to 1917 with the Orchestra of La Scala conducted by Carlo Sabajno, Remo Andreini as Rodolfo and Gemma Bosini as Mimì. Thomas Beecham, who worked closely with Puccini when preparing a 1920 production of La bohème in London, conducted a performance of the opera in English released by Columbia Records in 1936 with Lisa Perli as Mimì and Heddle Nash as Rodolfo. Beecham also conducted the 1956 RCA Victor recording with Victoria de los Ángeles and Jussi Björling as Mimì and Rodolfo.

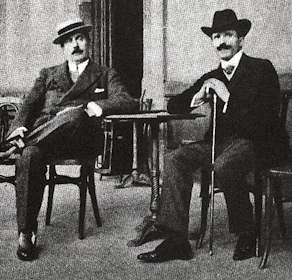

A.Toscanini and G. Puccini, ca. 1900

The only recording of a Puccini opera by its original conductor is by Arturo Toscanini who conducted the world premiere of the opera: this recording (RCA Victor 1946) features Jan Peerce as Rodolfo and Licia Albanese as Mimì.

Enrico Caruso, who was closely associated with the role of Rodolfo and worked with Puccini many times, recorded the aria “Che gelida manina” as early as 1906. A handful of cylinder recordings can be found on the UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive

A full list of recordings can be found at this page.

Film versions

Again, La Bohème inspired a number of cinematic versions, the first one as early as in 1916 directed by Albert Capellani.

And then in 1926 by King Vidor, in 1935 by Paul L. Stein, in 1945 by Marcel L’Herbier, in 1988 by Luigi Comencini. A full list can be found in the IMDB archive.

Final thoughts

Despite the popularity of La bohème, Puccini has been criticized on it over and over, sometimes by famous colleagues: the composer Benjamin Britten wrote in 1951, “[A]fter four or five performances I never wanted to hear Bohème again. In spite of its neatness, I became sickened by the cheapness and emptiness of the music.” [2]

I could not disagree more with Britten. I could hear it over and over again and never get sick of it. It is, simply, one of the most perfect operas in history.

Sources:

[2] Benjamin Britten: “Verdi – A Symposium,” Opera magazine, February 1951, pp. 113–114

Martin Kalmanoff: Aria from the “Missing Act” of La Bohème, Opera Quaterly, 1984

Statistics by operabase.com

Pictures:

Poster for the 1896 production for Puccini’s La bohème by Adolfo Hohenstein (1854-1928), Publisher: G. Ricordi & Co. (Allposters) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Puccini and his librettists [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Poster for the premiere of Leoncavallo’s La bohème [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Performance picture by Cebula (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Puccini and Toscanini picture by Menerbes (Archives Arturo Toscanini, Parma) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Publicity still from King Vidor’s 1926 movie from MGM [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

About the author

Gianmaria Griglio

Composer and conductor, Gianmaria Griglio is the co-founder and Artistic Director of ARTax Music.

Interested in some more music? Take a look at this series!