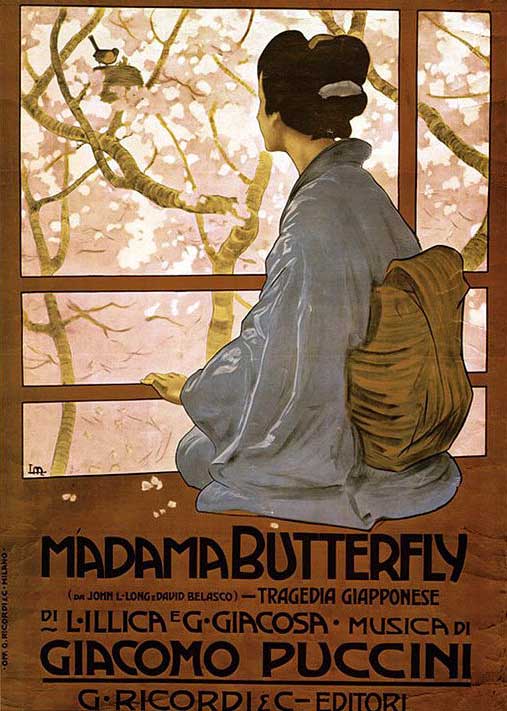

Puccini A to Z – M as in Madama Butterfly

Madama Butterfly, a Japanese tragedy

Genesys

Puccini chose the subject of his sixth opera after attending, at the Duke of York’s Theater in London in June 1900, a performance of Madame Butterfly, a one act drama by David Belasco. Belasco had, in turn, took the subject for his drama from a story by American John Luther Long, titled Madam Butterfly, published in 1898. Puccini did not speak or understand English, nor was he ever in Japan, but was so impressed with the emotional drama of the play that he felt compelled to set it in music.

The composition started in 1901 and proceeded with several interruptions, one of them being the famous car accident occurred on February 25th, 1903. The orchestration was started in November 1902 and completed in September of the following year and only in December 1903 the work could be said to be complete in all its parts. The opera premiered on February 17th, 1904, almost exactly one year after the accident.

The libretto was the result of the hard work of his favorite couple of librettists: Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa: the three of them had already successfully worked together on masterpieces like La bohème and Tosca and both Illica and Giacosa knew how demanding Puccini could be. This time, the research went even deeper: Illica even traveled to Nagasaki to better understand the local culture. Puccini, on his part, spent a lot of time researching Japanese music, getting help from a well-known Japanese actress, Sada Yacco, and from the wife of the Japanese ambassador to Italy. The latter also provided him with some sheet music of original folk songs and sang some of them for him.

Debut

On the evening of February 17, 1904, in spite of the expectation of its interpreters (Rosina Storchio, at the height of his career, Giovanni Zenatello and Giuseppe De Luca, as well as conductor Cleofonte Campanini), Madama Butterfly clamorously flopped at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

Ramelde, one of Puccini’s sisters, described the event in a letter to her husband:

“We went to bed at 2 in the morning and I could not close my eyes; we were all so sure! Poor Giacomo, we never saw him […] I did not hear the second act at all, and we ran out before the end of the opera“.

The most credited thesis to explain the fiasco is the conspiracy one: it was certainly believed by Ricordi and by Puccini himself that it was due to a plotting scheme to discredit the composer that the opera did not succeed on its debut. Well, after all, Puccini always had and still has his detractors. The same Madama Butterfly was described, by one of the critics attending the first production of the opera at the Arena of Verona in 1978, as “sentimental bourgeois, candy-floss in the melody and faded Japanese postcards“.

Puccini, at the time, wrote to his friend Camillo Bondi about the hateful atmosphere he could perceive at La Scala:

with a sad but strong mind, I tell you it was a real lynching. They did not hear a note, those cannibals. What a horrible orgy of people drunk with hate. But my Butterfly remains what it is: the most felt and evocative work I’ve ever conceived. And I will have the revenge, you will see, if I will perform it in an environment less saturated by hatred

Madama Butterfly: revisions

The flop at La Scala pushed both Ricordi and Puccini to withdraw the production and start a revision of the score. A large part of the first act was cut, making for a better flow; Pinkerton was given a new aria, “Addio, fiorito asil”; and the whole musical part of the suicide scene was revised.

In this new version, Madama Butterfly was presented at the Teatro Grande of Brescia three months later where it was a big success. Puccini kept working on smaller revisions: a third version was presented on January 2nd, 1906 at the Teatro Regio of Turin, conducted by Arturo Toscanini. The American premiere took place at the Metropolitan Opera House of New York in 1907, with Enrico Caruso as Pinkerton and Geraldine Farrar as Butterfly.

More changes came in 1920, when Puccini put back in a solo of Yakusidé, Butterfly’s drunk uncle. It’s possible that this was due to reasons other than musical: theaters fell into the habit of cutting a small concertato, the only appearance of Yakusidé in the 1907 revision, in order to save on the salary of one singer. Ricordi never published the 1920 version and today the practice of cutting the concertato still goes on in many productions.

Act I

On the flower-filled terrace of a Japanese house overlooking the harbor

Pinkerton, a US Navy Lieutenant, takes as wife Cio-Cio-San, a 15 years old geisha. The wedding is celebrated according to the Japanese law which gives Pinkerton, at any given time, freedom to disown his Japanese wife to take an American one.

Pinkerton is not moved by love (though he does grow a certain infatuation for Cio-Cio-San), but by vanity and spirit of adventure. The girl, on the other hand, falls for him completely, causing the rage of her uncle who accuses her to have abandoned her culture and her family, eventually disowning her. In the final duet of the first act, Madama Butterfly is consoled by a gentle Pinkerton, finding reassurance in his tender words of love.

Act II

Three years later, in Butterfly’s house

Shortly after the wedding, Pinkerton sails back to the States leaving Butterfly alone with her loyal servant, Suzuki. Despite Suzuki’s doubts, Butterfly is certain that her husband will come back as promised.

However, Pinkerton has, in fact, taken an American wife, Kate. During the years, he kept in touch with the American consul, Sharpless, and begs him to unfold to Butterfly the situation.

Everyone around her sees the situation for what it is, but her faith in her husband is unwavering: Butterfly refuses an offer to marry a rich lord and shows Sharpless her three years old son: the resemblance with Pinkerton is remarkable. At one point the harbor’s cannon fires, announcing the arrival of Pinkerton’s ship. Butterfly, excited to find confirmation of her faith in Pinkerton, orders Suzuki to prepare the house to welcome him back.

Act III

Dawn the next day, in Butterfly’s house.

The wait for Pinkerton stretches through the night. Pinkerton, informed about the existence of a son, goes to the house accompanied by Sharpless with the intention of taking him away to the US and educate him the western way. But he doesn’t have the guts to face Butterfly who fell asleep waiting for him. Instead, he asks Suzuki to intercede for him and leaves the scene once again.

Butterfly wakes up and shortly but surely realizes the truth: her happiness, her love story was nothing but an illusion. Her entire world collapses. Deprived of everything, she decides to give up her son so that he could have a future in the US, provided Pinkerton would come and get him himself. She asks to be left alone and, after sending her son to play, takes her own life with her father’s dagger. Pinkerton rushes back only to find her dead.

Geraldine Farrar as Madama Butterfly, 1907

Life circumstances

The composition of Madama Butterfly coincides with a tormented period in Puccini’s life: on January 19th, 1901, Giuseppe Verdi died: Verdi, 88, had been a giant in the operatic scenario for more than 50 years and also one of the first endorsers of Puccini. His death marked Puccini on a personal level as well as artistic, passing to him, de facto, the scepter of the last and greatest Italian opera composer. It was an honor for Puccini, but also a huge responsibility.

On top of it, his private life was in shatters: a well-known Casanova, Puccini was having affairs everywhere, to the point that his editor, Giulio Ricordi, wrote him a long letter insisting he’d stop wasting time with women and went back to his music (letter from Ricordi to Puccini of May 31st, 1903). Puccini tried to calm down, married Elvira Bonturi (with whom he had been in a relationship for 20 years) and managed to continue working and finishing Butterfly, despite being in a wheelchair because of the car accident occurred a few months earlier.

Curiosities

The first Japanese soprano to take on the role of Madama Butterfly was Tamaki Miura, who debuted the role in 1915 at the London Opera House. Miura became then an appreciated interpreter of Cio-Cio-San everywhere in the world: despite the lack of a big voice, according to the newspaper “Il popolo Toscano”, “the passionate and sorrowful character of Butterfly emerges in the graceful and sentimental figure of Miura alive and thrilling, moving and engaging” (March 2nd, 1921).

The American National anthem, which makes its appearance more than once in the opera, was, in Puccini’s time, the anthem of the US Navy. It only became the National anthem in 1931.

The first production of the original 1904 version of the opera took place in the same theater that had flopped it: La Scala of Milan, in 2016.

A comprehensive list of recordings can be found on this page. The UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive offers some digitalized cylinder recordings dating back as early as 1910. A copy of the libretto in Italian with English translation is available here.

Sources and resources:

The Centro studi Giacomo Puccini published in 2005 a book gathering all information and documents relevant to the genesis of Madama Butterfly: the book, titled “Madama Butterfly. Fonti e documenti della genesi” was written by Arthur Groos, Virgilio Bernardoni, Gabriella Biagi Ravenni, Dieter Schickling.

Cover photo by Sorasak; back phot by Andre Benz

Posters by Adolfo Hohenstein and Leopoldo Metlicovitz

Geraldine Farrar picture

About the author

Gianmaria Griglio

Composer and conductor, Gianmaria Griglio is the co-founder and Artistic Director of ARTax Music.

Interested in some more music? Take a look at this series!